“My Brother Moochie” author Issac J. Bailey talks about overcoming trauma

“What doesn’t kill you will make you stronger – only if you make it make you stronger.”

Issac J. Bailey repeated the line so often it became a refrain in what at times seemed like a long-form poem that defied genre.

“Trauma doesn’t make us stronger,” he said to a packed house Monday night at Spartanburg Methodist College. “It can cripple us. It can maim us. It can make us disconnected from other people and even frankly from ourselves. It can make us forget how beautiful and wonderful and worthy we always are and always have been.”

Bailey, a journalist who teaches at Davidson College, told how he cowered in a corner at 6 years old while he watched his father beat his mother, with painful recollection of the “sound of fists on flesh” and feelings of powerlessness.

He didn’t know what to do. The question wasn’t asked, but automatically comes to mind: What could anyone have done in that situation, particularly so young?

Fortunately, Bailey had a hero: His big brother, Moochie. Moochie was big and strong, and he dragged their father away, one of the many times he saved their mother. Bailey said Moochie saved him many times, too.

But three years later – in 1982, when Bailey was 9 – Moochie was arrested and later convicted of stabbing a white man to death. Bailey and his family would watch as Moochie was shackled and taken away. Moochie spent the next 32 years in prison, seven of them in solitary confinement.

In many ways, Bailey found himself in a prison, too. He wasn’t behind bars. But he was trapped by fear, by shame, by pain.

Bailey went on to write an autobiography, “My Brother Moochie,” about his family trauma. The book was selected for all SMC freshmen to read as part of their first-year experience.

After Moochie was taken away, Bailey said his speech got so bad he “couldn’t even put two words back to back.” He struggled with stuttering for 25 years, and eventually started having violent visions and dreams involving his wife and children. When he finally told his wife, she pressed him into therapy and Bailey was diagnosed with PTSD.

It was the post-traumatic stress disorder had made him a prisoner in his own mind.

“For so many years, I let my fears shrink me. I let my fears control me. I thought that they were too big and too strong for me,” Bailey told students.

“And then my shame jumped up and made it worse. When you are a black dude, in the South, and your oldest brother is in prison, your youngest brother is in prison, two other brothers are in prison, it shames you into silence. Because it convinces you that all those ugly things that people say about people like you must be true. And it hurts like hell. And for the longest time, I allowed those fears and that shame to cripple me, to silence me.”

Bailey tells the story of his life with an eloquence that at times masks the stutter he still struggles with. It becomes more apparently during question-and-answer sessions, when he has to come up with a reply off the cuff.

Mequil Waller, a 19-year-old freshman from Spartanburg, said Bailey’s discussion of PTSD both in his book and in his talk at Camak Auditorium resonated with him. He recalled his own mother, raising three children and moving from house to house, and his sister who didn’t always make the best choices when she was younger.

He said he appreciated Bailey’s plea to the students to find the strength to confront their fears – and to seek help when they are in pain.

“That was really helpful,” said Waller, an art major who plans to eventually study jazz. “I’ve had it preached it to me a lot due to my situation: ‘Hey, you need to talk to people, you need to be more expressive.’ I’ve had that a lot. And this was more of a refresher, and I enjoyed it.”

David Hawkins, a 19-year-old freshman who is considering majoring in English, said he was impressed with the way Bailey commanded the stage, regardless of his stutter – the way he not only confronted his speech issues head on, but that he put himself in a place that frightens most people: public speaking.

Hawkins, of Spartanburg, said he related to parts of “My Brother Moochie.”

“I come from an impoverished background, so reading about his college life made we wish more students were exposed to stories like his,” he said. “I know all the financial baggage I came in with, so I can’t imagine how difficult his experience would have been, especially so soon after Jim Crowe.”

(Jim Crow laws were enforced through the mid-1960s; Bailey was born in the early ’70s.)

Teresa Ferguson, Dean of Students and Vice President for Student Development, selected “My Brother Moochie” for this year’s freshmen. She had heard Bailey speak before, and wanted students to hear his message. She said she could tell from the students’ questions that Bailey’s responses made them feel better about things they may be going .

“Bailey’s story emphasizes seeking support when you are struggling, and that is a message we share with our students,” Ferguson said. “We are here to support you at SMC. All students, regardless of their background, are struggling with something. Remember: You don’t have to go it alone.”

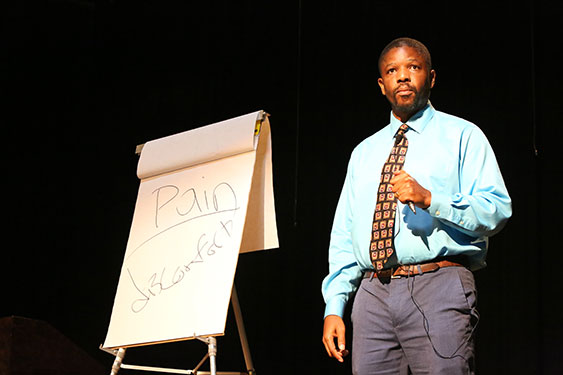

Bailey has ramped up his public speaking over the past five years, using techniques like roaming the stage and jotting down words on a board to act as cues. He said he often gets messages from students after his talks, mostly from those who didn’t ask questions in the public Q-and-A.

Bailey closed the night with a plea to students to grab their fears “by the neck and wrestle them down.” He reminded them it took him 25 years to get help, a choice that became increasingly harder to live with. He told them that if they were in pain, they needed to make a choice to get help “right now.”

“At some point, life forces us to choose: Either my fears will shrink me, or I will shrink my fears,” he said. “Whatever challenges you face, whatever fears that haunt you, whatever scars you have deep on the crevice of your souls, you are still beautiful enough to overcome that. You are still worthy of being loved and being successful.”

And then the refrain: “Because what doesn’t kill you will make you stronger – only if you make it make you stronger.”